Humans have long been drawn to space as part of our search for meaning, significance and security. But what if space could be the source of our salvation?

It is this question that led Brandon Reece Taylorian, widely known by his mononym Cometan, to start a new religion: Astronism.

From astrology to astrotheology, from questions of how to practice religions ensconced in Earth’s realities and rhythms to the context of outer space or life on other planets to the creation of new religious movements, spirituality and space exploration have long been intertwined.

It is Astronism, perhaps, that has taken the relationship between outer space and religion to its logical limit. At the age of 15, Cometan began to craft an astronomical religion that “teaches that outer space should become the central element of our practical, spiritual, and contemplative lives.”

“From my perspective, how religion and outer space intersect is crucial to understanding the future of religion,” Cometan, who is also a Research Associate at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, told me. “Outer space is the next great frontier that will reshape the human condition, including our religions.”

To that end, Cometan has contemplated how space exploration might produce new forms of insight, revelation and spiritual experience.

“The further we dare to venture beyond Earth, the more our beliefs about God and the universe will transform. I think that we need new and bold religious systems that will inspire our species to confront and overcome the challenges of the next frontier,” he said.

“As an Astronist, I define outer space as the supreme medium through which the traditional questions of religion will be answered.”

In this edition of “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I feature a Q&A with Cometan about Astronism and what we might have to learn about religion – and how we define and study it – through his experience founding a new tradition drawn from the stars.

A Tale for our Time: Shira Piven and Joshua Salzberg on “The Performance”

It was not an ideal spot for a phone call but there I was, balancing between cars on a train traveling back home to Berlin, talking with Joshua Salzberg, who was calling from Budapest, where he was working on a film.

Salzberg knows I am a religion nerd. The film he adapted with co-writer/director Shira Piven — “The Performance”— featured a cast of characters with varying religious identifications. The team wanted to get the details right. Down to the minutest items.

So, there I was, rocking back and forth as the German state of Brandenburg flitted by, talking to Salzberg about the ring a club owner in 1930s Berlin might foreseeably be wearing.

That attention to detail impressed me. The care and concern that Piven, Salzberg and the entire team brought to the film is a testament to its overarching message of resisting hate and finding people’s humanity in the unlikeliest of places.

“The Performance,” starring the director’s brother, Jeremy Piven of Emmy-nominated “Entourage” acclaim, is adapted from an Arthur Miller short story of the same name. The story has been described as, “a strange midnight train ride” by Seattle Times critic Richard Wallace, and tells the tale of Harold May, a down-on-his-luck New York tap dancer who heads to Europe in the 1930s in search of new opportunities.

While dancing on the tabletops of a Hungarian night club, May and his troupe attract the attention of Damian Fugler (Robert Carlyle), who invites them to give a special performance at a Berlin nightclub, hefty paycheck included. May, who is Jewish but can “pass” as a blond-haired Aryan, and his fellow performers — including Adam Garcia as the politically attuned Benny Worth, Isaac Gryn as a closeted Paul Garner, Lara Wolf as the namesake of a Persian princess “Sira” and Maimie McCoy as a recently divorced, single dancer Carol Conway — are fast-tracked through a series of ethical, moral and professional through stations as they tap their way into a performance none of them really want: a private show for Adolph Hitler.

The story chugs along like “a modern, gothic folktale,” with the personal stakes becoming ever greater until it all falls off the rails, when their experience of opulent luxury at the behest of their German hosts contrasts too starkly with the increasingly evident persecution of Jews, homosexuals and other so-called “undesirables” around them.

Image And Power, Satire And Sacrilege At The Paris Olympics

When I teach a religious studies class, I try to pull something from the headlines to use for discussion. You know, something religion-y to get students thinking about religion’s continuing ubiquity and importance in the world today.

Had I been teaching a class at the end of July 2024, there would have been only one option for that thing: the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics.

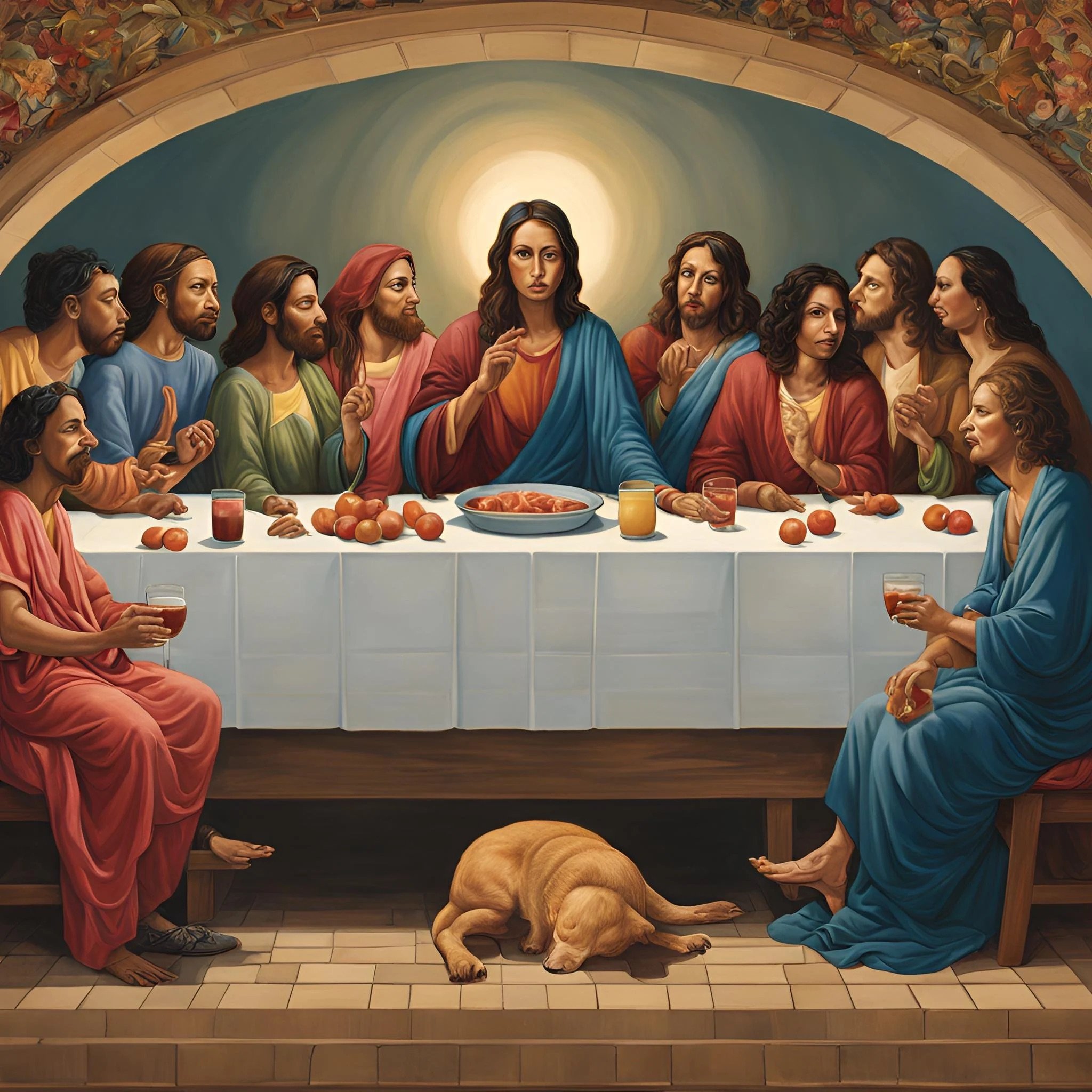

Not the bells ringing at Notre Dame Cathedral and not Sequana, goddess of the river Seine, galloping in gleaming silver with the Olympic flag. Worthy topics, to be sure. But none was more worthy of discussion — if social media were the measure of things — than a living tableau of LGBTQ+ performers posing in what seemed to be (or…possibly not) a recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

It created some conversation and controversy, to say the least. And rather than adjudicating the right- or wrongness of the artistic choice, the ins and outs of the potential offense, whether the portrayal was Ancient Greek or Renaissance Italian, or the dynamics of French secular culture, global Catholicism and U.S. evangelical culture (again, all worthy topics), I would have used the kerfuffle as a case study in the power of the image and the power of satire in the world of religion.

The power of image

With or without religion, images are powerful. They move us to anger, they move us love; they move us to buy, they move us to believe.

And in his eponymous book, religion scholar David Morgan discusses the power of the “sacred gaze” — a way of seeing that invests an object (an image, person, time or place) with spiritual significance. Across a variety of religious traditions, Morgan traces how images in different times and spaces convey beliefs and produce religious reactions in human societies – what he calls, “visual piety.”

As human products, images and religious ideas have grown together, with some images having the power to determine personal practice and identifications, rituals and notions of sacred space. As “visual instruments fundamental to human life,” images have their own materiality and agency. Think of the ubiquitous statue of the Buddha sitting in backyard or the glittery gold calligraphy of “Allah” or “Muhammad” hanging over a family’s living room; the brightly colored images of Ganesha and Krishna or a copy of Eric Enstrom’s “Grace” hanging in kitchens and cookhouses across the U.S.

Each of these images serve as markers of a whole range of social concerns, devotional piety, creedal orthodoxy or gender norms.

So too with da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” As one of the most well-known religious images the world over, the painting is not a part of any Christian canon. It isn’t even an accurate representation of what the Last Supper, as recorded in the Christian Gospels, would have been. Jesus’ disciples were not Renaissance European white men, they were probably not pescatarians, nor were they seated on one side of the table (or seated at that kind of table at all). But as a myth we knew we were all making, and as the National Gallery’s Siobhán Jolley pointed out on X, the painting morphed from being a sign (a painting portraying an interpretation of biblical texts) to a signifier (a bearer of meaning so pronounced that it came to visualize Jesus’ last meal with his followers for many).

And in our contemporary culture(s), such visual cues carry a particular kind of power. In a highly visual society, bombarded by the rapid consumption of images on screens of varying size and intensity, images can transcend one context and speak to many — as did the recreation of da Vinci’s “Last Supper” (or…maybe not) when it resonated both positively and negatively with so many.

As a visual quotation of a popular image, we translated its meaning and the image spoke with power to various communities and subcultures. It tore people up and took the internet by storm. It manifested opprobrium and offense, celebration and adulation, as it was read as a sacrilege of the highest offense or as a symbol of vibrant tolerance and pleasing subversiveness. Along the way, it created a whole range of responses, on what is and what is not offensive, what is and is not idolatry, what is and is not Christian privilege, what is and is not persecution; the list could go on and on.

For all that it was (or was not), the Opening Ceremony moment (and it was, after all, but a blip on the screen) illustrated once again the power of religious images, even in increasingly secular societies.

The power of satire

In addition, whatever the performance was meant to represent, it was almost certainly meant as a form of satire.

A genre with generations of history, religious satire’s power lies in its ability to direct the public gaze to the vice, follies and shortcomings of religious institutions, actors and authority writ large. Whether calling out hypocrisy or corruption, religious satire has been used for centuries to take religious elites or established traditions to task.

Examples of savage satire and nipping parody abound across religious history. From the Purim Torah and its humorous comments read, recited or performed during the Jewish holiday of Purim to "Paragraphs and Periods,”(Al-Fuṣūl wa Al-Ghāyāt) a parody of the Quran by Al-Ma‘arri or the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer or Robert Burns’ poem “Holy WIllie’s Prayer,” authors and authorities, playwrights and poets have wielded scalding pens to critique what they see as the hypocrisy, self-righteousness and ostentation of religious communities.

As such, satire has been powerful as a means of protest both from without and within religious traditions. For example, the 16th-century rebel German monk and Reformer Martin Luther used his caustic touch to call what he thought were abuses within the Catholic Church to task. Jeering and flaunting his way through theological controversies and the dogmatic discussions of his day, Luther was not one to skirt the issue or back away from using humor and satire to prove his point. In fact, he was well known for his use of scatological references, offending his followers and opponents with vulgar references to passing gas and feces.

Each of these examples shows how satire relies on a combination of absurdity, mimicry and humor to highlight the problems its creators see with religious actors’ or institutions’ behaviors, vices or social standing.

To that end, the opening ceremony’s display was religious satire par excellence, insofar as it pushed a particular social agenda and advocated for certain recognitions for a marginalized community through its exhibition. The living display not only created a stir but captured the public imagination, sparking discussion and debate about Christian privilege, European culture and the acceptance and affirmation of LGBTQ+ individuals in religious communities. In this way, religious satire can also help create community and a sense of belonging among those who are in on the joke and jive with the critique embodied in the satire.

The persistent power of religion

The debate around the tableau will (hopefully) die down in the days and weeks to come (and perhaps already has in a media cycle that serves up a fresh controversy every 24-hours). But if I were to point to just one lesson in my religious studies classroom, I would highlight how the scene — for all it was or wasn’t — proved once again the power of images and satire in the field of religion.

It is another case study in how, even at supposedly “secular” events in a decidedly “secular” country, religion — and the primary and secondary images and satire thereof — remains persistently present and ubiquitously potent. And that, dear students of religion, is something to keep in mind for the next controversy, which is sure to come sometime soon.

Feast or fast, food and faith

“You’d think we’d lose weight during Ramadan,” said Amina, a registered dietician who observes the Islamic month of fasting each year in Arizona, “but you’d be wrong.”

Ramadan, the ninth month of the lunar calendar, is a month of fasting for Muslims across the globe. Throughout the month, which starts this year around March 11, observers do not eat or drink from dawn to sunset.

“It sounds like a recipe for weight loss,” Amina said, “but you’d be wrong. I’ve found it’s much more common for clients — of all genders and ages — to gain weight during the season.”

The combined result of consuming fat-rich foods at night when breaking the fast (iftar), numerous celebratory gatherings with family and friends, decreased physical activity and interrupted sleep patterns means many fasters are surprised by the numbers on the scale when the festival at the end of the month (Eid al-Fitr) comes around.

Christians observing the traditional fasting period of Lent (February 14 - March 30, 2024) can also experience weight gain as they abstain from things like red meat or sweets. Despite popular “Lent diets” and conversations around getting “shredded” during the fasting season, many struggle with their weight during the penitential 40-days prior to Easter, the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection.

The convergence of the fasting seasons for two of the world’s largest religions meet this month, and people worrying about weight gain during them, got me thinking about the wider relevance of food to faith traditions.

And so, in two pieces — one for ReligionLink and the other for Patheos — I take a deeper look at how foodways might help us better understand this thing we call “religion” more broadly.

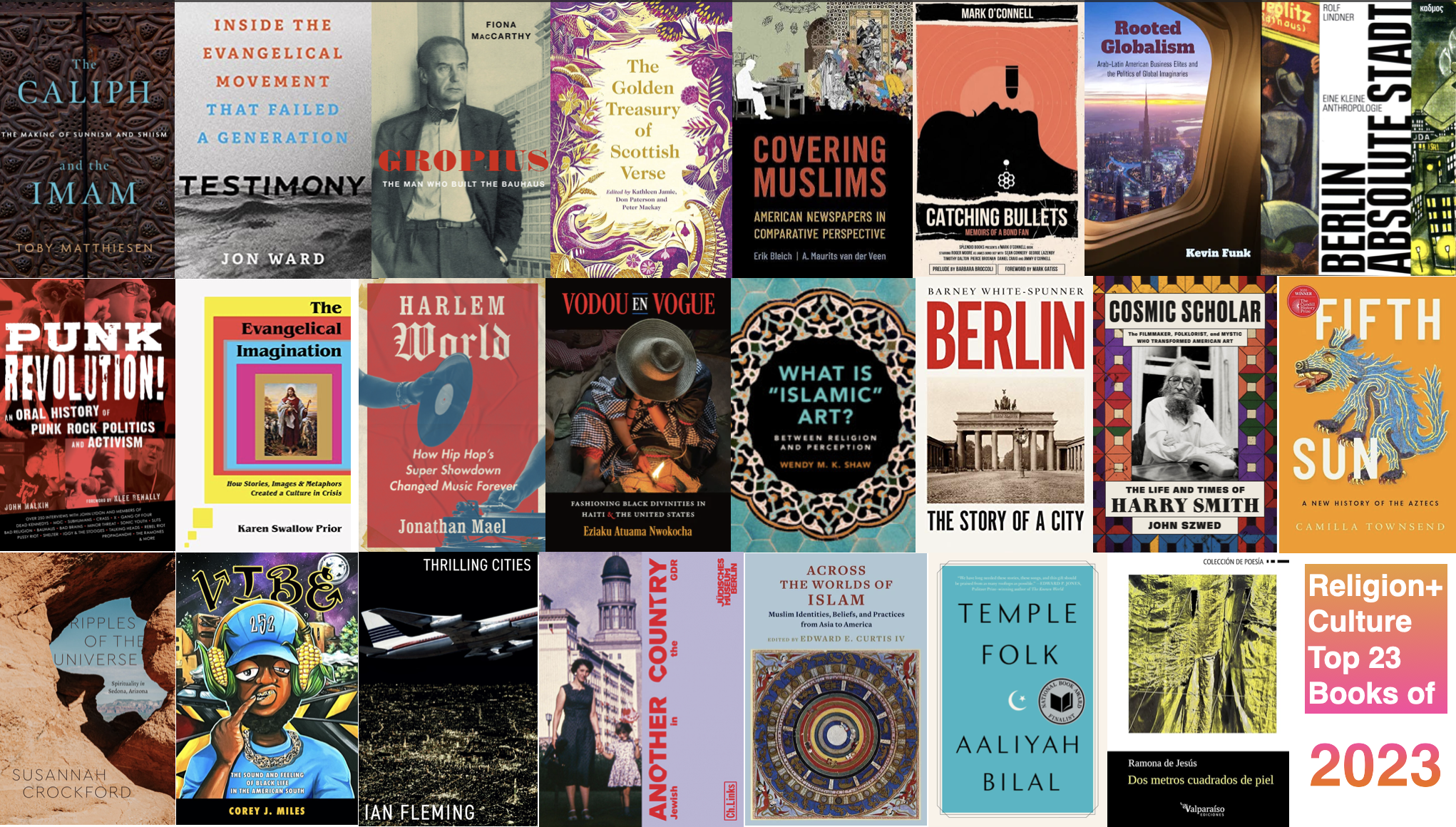

Religion+Culture Top 23 Books of 2023

When I started 2023, I was on a high. Maybe you were too. Maybe, like me, you were thinking, “Wow, 2023 is going to be…amazing!”

But as I snuck outside of the house in the Swedish countryside where I was celebrating the New Year with friends, I made a phone call that immediately changed things.

All the plans, dreams, and hopes for the year to come were put on hold. Or, at least, on standby.

As 2023 unfolded, we lost loved ones. We witnessed some pretty horrible moments around the world. Our families changed forever. Life transitions came and went. And as the year comes to a close, we realize nothing is going to be the same. The earth has shifted. The tectonic equations of how to navigate this life have changed.

The way 2023 played out meant that I didn’t read as much as I usually would over the year. I wasn’t as productive. The pages weren’t turned as quickly.

Nevertheless, these books saw me through. Amidst the change, I turned to wisdom and insight from authors who knew better than me. I enjoyed some fun ones too — books that took me out of where I was and helped me imagine another world.

After all, that is the power good books hold.

I hope, no matter what 2023 was like for you, that you had the chance to read some good books.

Whether the year was wonderful, the worst, or decidedly in between, I hope reading helped you get here. I know I wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for the books I’ve read, in 2023 or any other year.

And so, without further adieu, here are my top 23 books of 2023 (some new, some old), in the order I read them:

The Caliph and the Imam, by Toby Matthiesen (2023) - A monumental review of the 1,400-year-long complicated relationship between Sunni and Shii.

Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Failed a Generation, by Jon Ward (2023) - In this enlightening memoir, Ward recounts a life caught between being an evangelical and being a political correspondent.

Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus, by Fiona McCarthy (2019) - A detailed recounting of the life of a man who helped make late-modernity what it is.

Covering Muslims: American Newspapers in Comparative Perspective, by Erik Bleich and A. Maurits van der Veen (2023) - Testing to what extent stories about Muslims are negative in comparison to average media coverage, the authors find the bulk to be “resoundingly negative.” The question remains, what are we going to do about it?

Catching Bullets: Memoirs of a Bond Fan, by Mark O’Connell (2012) - “A unique and sharply-observed love-letter to James Bond.”

The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse, edited by Kathleen Jamie, Don Paterson and Peter Mackay (2021) - You haven’t lived until you’ve been able to discern the resonant meaning of a Gaelic ballad.

Rooted Globalism, by Kevin Funk (2022) - Funk’s book sheds fresh light on the landscapes of interconnection between Latin America and the Middle East and the economic, political, and social orders that animate them.

Berlin: Absolute Stadt, by Rolf Lindner (2016) - Shines a stark light on the simultaneity of city and people, technical and mental change, that defines the character of Berlin and Berliners.

Punk! Revolution: An Oral History of Punk Rock Politics and Activism, by John Malkin (2023) - A riveting insiders’ history of punk’s charged relationship with social change.

The Evangelical Imagination, by Karen Swallow Prior (2023) - A perceptive analysis of the literature, art, and popular culture that has shaped what evangelicalism is and provides fodder to reimagine what it might become.

Harlem World: How Hip Hop’s Showdown Changed Music Forever, by Jonathan Mael (2023) - Mael unpacks how lyrical flair, and new techniques like record-scratching, elevated hip hop from the city’s streets to airwaves across the world.

Vodou en Vogue: Fashioning Black Divinities in Haiti and the United States, by Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha (2023) - An innovative take on how fashion shows religion to be a “multisensorial experience of engagement with what the gods want and demand.”

What is ‘Islamic’ Art? by Wendy M. Shaw (2019) - Shaw adroitly explores the perception of arts through the discursive sphere of historical Muslim texts, philosophy, and poetry.

Berlin: Story of a City, by Barney White-Spunner (2020) - As the title promises, this is a narrative retelling of how Berlin came to be “Berlin.”

Cosmic Scholar, by John Szwed (2023) - Brilliantly captures the life and legacy of the enigmatic filmmaker, folklorist, painter, producer, anthropologist, archivist, Kabbalist, and alchemist Harry Smith (1923–1991).

Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs, by Camilla Townsend (2019) - Dispels some of the most long-lasting myths about Mexica culture, in an approachable and convincing manner.

Ripples of the Universe: Spirituality in Sedona, Arizona, by Susannah Crockford (2021) - An intimate portrait of the politics, economics, and everyday realities of New Age spirituality in the northern Arizona tourist town.

Vibe: The Sound and Feeling of Black Life in the American South, by Corey J. Miles (2023) - Deeply and deftly examines Blackness in the American South through the prism of “trap music.”

Thrilling Cities, by Ian Fleming (1959) - A timepiece of travel writing from the creator of James Bond.

Another Country: Jewish in the GDR, by the Jewish Museum of Berlin (2023) - A revealing exhibition book that explores what it was like to be Jewish in East Germany.

Across the Worlds of Islam: Muslim Identities, Beliefs, and Practices from Asia to America, edited by Edward E. Curtis IV (2023) - Centers the stories of Muslim practices, perspectives and people too often marginalized in both popular and academic imagination.

Temple Folk, by Aaliyah Bilal (2023) - A compassionate collection of stories that shows the humanity of the Nation of Islam — its faults, foibles, and the people who fell between.

Dos metros cuadrados de piel, by Ramona de Jesús (2021) - Raw, honest, and — in the truest sense of the word — poetic to the bone.

A bust of Martin Luther in Eisleben, where he was born, baptized and died. Shortly before his death on 18 February 1546, Luther preached four sermons in Eisleben. He appended to the second to the last what he called his "final warning" against the Jews. (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

A critical look at Luther Country

It’s pretty boujee, but I have two stained glass windows in my office.

I know, I know.

But one of them is pretty much tailor made for a religion nerd like me. It’s a bright and beautiful, stained-glass representation of the Wartburg Castle.

Perched at a height of some 400m above delightful countryside and rich central German forest, south of the city of Eisenach in Thuringia, the Wartburg is “a magnet for memory, tradition, and pilgrimage,” a “monument to the cultural history of Germany, Europe, and beyond.” Christians the world over also know the castle as where Martin Luther made his momentous translation of the Bible over the course of eleven weeks in the winter of 1520-21.

Since moving to Eisenach, I’ve watched out my windows — the non-stained ones — as busloads of tourists from places like South Korea, the U.S., and Brazil arrive on the square outside my apartment, where a prominent statue of Luther awaits them. They are here, in Luther Country, to walk in the Reformer’s footsteps and learn from his life in towns like Wittenberg and locales like the Wartburg.

A lot of these tours lavish praise on Luther, lauding the 16th-century rebel monk and cantankerous theologian for birthing the Reformation, and shaping Germany and the wider world’s theological, linguistic, historical, psychological and political self-image in the process.

And rightly so. Luther’s legacy is long and important to understand. But I can’t help but wonder what these tours would look like if they were a bit more critical of the man and his consequence. What, I often muse, would a more critical Luther tour look like?

Who said anything about an apple tree?

As the annual Reformation Day approaches (October 31) and I get ready to host a group of college students in Eisenach here to learn about Luther and his impact, I’ve been thinking about how our vision of Luther can be skewed by the superficial stereotypes that are typically trotted out for people on the usual tours.

It’s not that I blame the tourists, travelers, and pilgrims themselves. It’s hard to see past the Luther-inspired gin, “Here I Stand” socks, and cute Playmobil toys to disrupt the narrative around the Reformator.

The well-known statue of Martin Luther in Lutherstadt-Wittenberg, in central Germany. Some commentators suggest it shows — with the word “END” written so prominently under the words “Old Testament” — a questionable view of the Bible “in a political and social context in which anti-Jewish views are again on the rise.” (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

But the resources are there, if we care to see them, to startle and awaken our appreciation for who Luther was in critical fashion – to move beyond the myths we know we are making to (re)evaluate Luther and the ways in which we’ve made him into a caricature for our own purposes.

We all make claims about ourselves and others, doing so from within practical, historical, and social contexts. Stories around Luther are no different. When we talk about Luther, it is less about the man, his thought, and his supposed authority over theology and history itself. Instead, it is much more about the ongoing process by which we humans ascribe certain things to people like him: certain acts, certain status, certain deference.

Many of the stories and claims about Luther have calcified over time, produced and reproduced in books and movies, within theological writings and on tours in central Germany.

The good news is, they have also been contested, undermined, and — in some instances — replaced.

Some of these have been relatively simple things, like the fact that Luther was no simple monk, but a trained philosopher and theologian. Or, that he never nailed ninety-five theses to a church door in Wittenberg or said, “Here I stand!” or anything about planting an apple tree. These are, as Dutch church historian Herman Selderhuis wrote, fine sentiments and sayings, but just not true or attributable to Luther himself.

Luther: Wart(burg)s and all

There are also darker and more difficult subjects in need of revisiting in our retellings of Luther’s life — issues that bear relevance to contemporary conversations around race and class, diversity and difference.

As PRI reported, appreciating who Luther was also means coming to terms with how he “wrote and preached some vicious things about Jews.” In his infamous 1543 diatribe “Against the Jews and Their Lies," Luther called for the burning of Jewish synagogues, the confiscation of Jewish prayer books and Talmudic writings, and their expulsion from cities. It is possible that these directives were immediately applied, as evidence suggests that Jews were expelled from the town of his birth, Eisleben, after he preached a sermon on the “obdurate Jews” just three days before his death at age 62.

Luther’s death mask in Halle, Germany (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

Dr. Christopher Probst, author of Demonizing the Jews: Luther and the Protestant Church in Nazi Germany, said that while Luther’s “sociopolitical suggestions were largely ignored by political leaders of his day,” during the Third Reich “a large number of Protestant pastors, bishops, and theologians of varying theological persuasions utilized Luther’s writings about Jews and Judaism with great effectiveness to reinforce the antisemitism already present in substantial degrees.”

Probst said that one theologian in particular, Jena theologian Wolf Meyer-Erlach, “explicitly regarded National Socialism as the ‘fulfillment’ of Luther’s designs against Jewry.”

Today, far-right parties continue to use Luther’s image and ascribed sayings to prop up their own political positions.

Beyond his tirades against Jewish people and their sordid use in German history, we might also take a critical look at the class dynamics at work in Luther’s life. Historically, his family were peasant farmers. However, his father Hans met success as a miner, ore smelter and mine owner allowing the Luthers to move to the town of Mansfeld and send Martin to law school before his dramatic turn to the study of theology. How might that have shaped the young Luther and later, his response to the Peasants War in 1524-25? How might it influence our understanding of who he was and what he wrote?

There are also critical gems to be found in his writings on Islam and Muslims, his encounters with Ethiopian clergyman Abba Mika’el or the shifting gender dynamics at work in his relationship with Katharina von Bora, a former nun who married Luther in 1525.

Reimagining Luther Country

Thankfully, I am far from the first person to point these things out. Museum exhibits, books, and documentaries have covered these topics in detail, doing a much more thorough job than I have above.

The problem is that gleanings from these resources can struggle to trickle down to the common tour or typical Luther pilgrimage. Or, they’re ignored in favor of just-so stories.

In Learning from the Germans, Susan Neiman wrote about the power of a country coming to terms with its past. In her exploration of how Germans faced their historical crimes, Neiman urges readers to consider recognizing the darker aspects of historical narratives and personages, so that we can bring those learnings to bear on contemporary cultural and political debates.

We might consider doing the same as we take a tour of Luther Country — whether in person or from afar. By injecting a bit of restlessness into our explorations, stirring constantly to break up the stereotypes, being critical and curious and exploring outside the safe confines of the familiar, we might discover more than we bargained for. But that, I suggest, would be a very good thing.

By telling different stories about Luther — and by demanding that we be told about them — I believe we might better know ourselves. How might we relate to a Luther who is not only the champion of the Reformation, but a disagreeable man made into a hero for political and theological purposes? How might that Luther speak to our times and the matters of faith and politics, society and common life, today?

As we come up on Reformation Day — and I welcome that group of students to my hometown and all its Luther-themed fanfare — I hope we might lean into such conversations and recognize how a critical take on Luther might prove a pressing priority for our time.

The New Zealand All Blacks celebrating after winning the 2011 Rugby World Cup in New Zealand (PHOTO: Flickr)

Religion at the Rugby World Cup

Rugby, Winston Churchill is supposed to have said, is a “hooligan’s game played by gentlemen.”

No doubt, rugby union is an aggressive, sometimes brutal, and incredibly demanding sport that pushes players’ bodies to the extremes: running, hitting, jumping, and grinding their way across the pitch for 80 minutes.

But what of their souls? How do these “gentlemen” (or women) bring their spirituality to bear in a sport many consider savage by nature?

In the lead-up to the Rugby World Cup (RWC) in France (September 8 - October 28, 2023), this month’s “What You Missed Without Religion Class” takes a look at how religion might play a role in the crowning of rugby’s world champions.

Within the field of religious studies, “religion and sport” research has traditionally focused on two areas: religion as sport and religion in sport. While one could make the case that rugby is religion in places like New Zealand, I consider what we might learn by looking at how the cultural phenomena of religion and sport intersect, overlap, and mimic each other in the wide world of rugby.

Faith and ‘footy’

Martin Lewis, a Christian chaplain for the Cardiff Blues — a professional Welsh rugby team — says that religion can play an important role in rugby players’ lives both on and off the pitch.

Lewis, a 6-foot-7 Welsh back-rower with more than 400 first class rugby matches behind him, said that even though spectators may not see it, faith influences some of the sports’ most prominent players.

For example, Sonny Bill Williams, one of New Zealand’s all-time greats, converted to Islam in 2009, saying it helped him find his way in the chaotic world of professional sport.

Since retiring from professional rugby, the former All Black has become a prominent spokesperson for Islam on Instagram and other social media channels, not only sharing his personal pilgrimage journey but speaking out on social justice issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the recent “abaya ban” in France. In the aftermath of the 2019 attacks on mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, his mother and fellow All Black Ofa Tu’ungafasi converted due in part to his guidance.

Another famous faith-fueled player is Jonny Wilkinson, whose iconic drop goal in the dying minutes of the 2003 World Cup final ensured his place in rugby union lore, winning England their only Webb Ellis trophy to date. But beyond the highlight-reel, Wilkinson told Men’s Fitness that anxiety, depression and burnout haunted his career. Being a practicing Buddhist helped him make sense of his own mental health and find “spiritual ways to become more grounded in the present moment.”

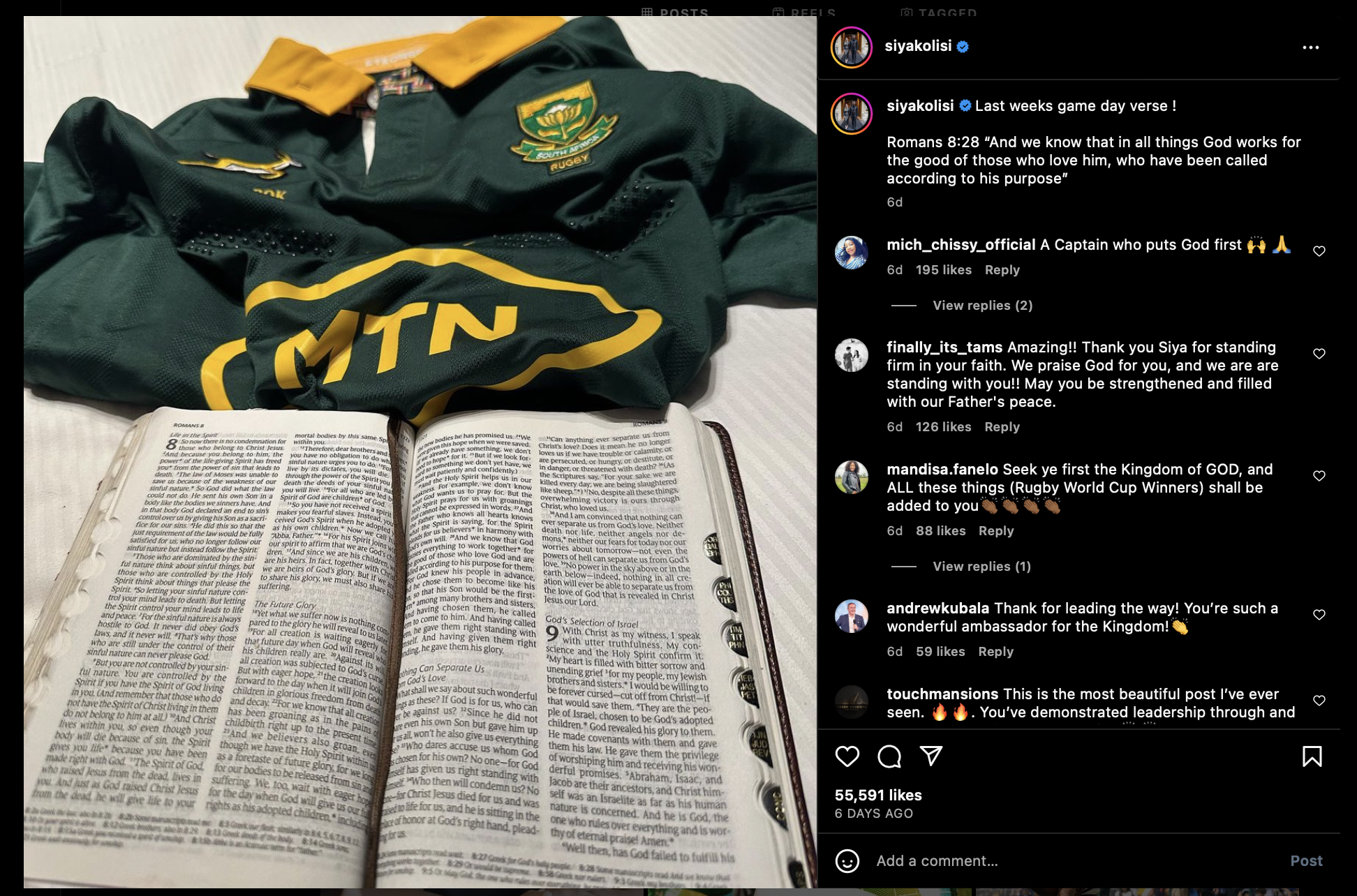

Several big names you’re likely to see at the RWC are also vocal Christians. Siya Kolisi, captain of the current world champions, the South African Springboks, said he was “born again” following a public saga when his wife found provocative photos of another woman in his Instagram messages. Kolisi said his newfound spiritual commitments helped him fight off temptation and make better lifestyle choices.

Kolisi claims Christianity has not only made him a better husband, but a better player and leader on the field. That claim was put to the test when he tore his ACL in April 2023, putting his ability to play at this year’s RWC at risk. But in what The Daily Mail called a “medical miracle,” Kolisi went from “surgeon’s table” to “being back fit” in three months. His faith inspired him during the turnaround, he said, as he asked for prayers from supporters and regularly posted Bible verses alongside photos and videos of the personal training routine that brought him back to the pitch in time for the team’s RWC warm-up matches.

For each game day, he posts a different Bible verse, sometimes with a picture of his jersey draped over his open Bible. Upon his return against Wales in August, he posted a video with the following caption on Instagram:

Deuteronomy 31:8-9 The Lord himself goes before you and will be with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged. Thank you Jesus ❤️🙏🏾Thank you for all the support [sic] and prayers through my rehab, im [sic] really grateful ❤️🇿🇦🙏🏾

It was liked over 62,000 times.

But religion can also cause controversy in the rugby world.

Israel Folau, a professional dual-code rugby player who has represented Australia and Tonga at the international level, was famously sacked by the Australian national rugby association after he paraphrased a Bible verse promising damnation for unrepentant "drunks, homosexuals, adulterers, liars, fornicators, thieves, atheists and idolators.” In other posts, Folau claimed transgender people were evil and that the devil was influencing governments to allow primary school children to change their gender.

Several fellow players supported Folau, defending his “religious freedom” and right to share his opinion in public fora. Others denounced his fundamentalist perspectives, including fellow Wallaby David Pocock, a Christian rugby rockstar and politician who has been an outspoken advocate for equal marriage rights for same sex couples and has called out homophobic abuse on the field of play.

Weeping Welshmen and post-game prayer

As a rugby chaplain, Lewis says it’s not his job to weigh in on such issues but focus on the individuals in front of him.

Lewis said he offers “well-being support” that is “pastorally proactive and spiritually reactive” to Christians, Muslims, or those of no faith at all.

Martin Lewis, rugby chaplain. (Courtesy Photo, Sports Chaplaincy UK)

“A lot of players are just looking for someone to talk to who isn’t their boss or a fellow player,” Lewis said, “and I’m there to have a chat and maybe offer a bit of advice.”

More than that, Lewis said he’s been a shoulder to cry on — literally — for some of Wales’ biggest players. “Being a chaplain is all about journeying with people,” he said. To that end, he’s performed funerals for players and their families, celebrated births and marriages, and even got a call from thankful parents who said his counsel helped save their son from suicide.

At this year’s RWC, Lewis said there won’t be any official chaplains like there were at the 2011 event. Instead, chaplaincy will happen in a more informal way, he said.

Nations like Fiji, Samoa, Namibia, and Tonga might even bring their own chaplains. “Some of their assistant coaches might even be pastors or spiritual leaders for the team,” he said, “and might lead prayer time or Bible study every day during training.”

Keen viewers might also catch players praying together on their knees before or after the game. Even players from different teams will often circle up and pray with one another, he said, “maybe even for forgiveness for the cheap shots they took at each other on the field.”

Off the field, churches are using the excitement around the event for outreach opportunities. Conversion stories like that of former Welsh international Brian Haywood have been translated into multiple languages to be handed out in the form of tracts and booklets at fan zones in France. Lewis himself will be hosting an event in advance of the RWC featuring the testimony of retired rugby player Nick Williams, first cousin of Sonny Bill.

Whether it’s outreach, outspoken players or pre-game rituals by fans and players seeking to bend the will of the rugby gods in their direction, religion will play a role at this year’s RWC.

The keen student of religion should take note.

As a sport chaplain, Lewis will be one of those observers. “Rugby is bringing in people from all over the world,” Lewis said “and many people come to the pitch with a faith background. You have to look after that.”

Asked to prophesy this year’s winner, Lewis doesn’t think he can discern the outcome. “The Springboks, All Blacks, and France are all looking pretty good,” he said, “but my heart has to stick with the Welsh.”

Given their recent form, that may take all Lewis’ prayers to prove true.

Does the world really need interreligious dialogue?

Growing up in what could best be described as a decidedly non-ecumenical Protestant denomination, I was taught to treat “interfaith” like a bad word.

But the negativity around interactions between people of different religious, spiritual and humanistic beliefs always sat a bit awkwardly with my everyday experience growing up in Los Angeles, one of the most religiously diverse cities in the United States.

I couldn’t square the alarming discourse around interreligious interactions with the lived reality of diversity that defined my teenage years (and beyond). My friends were Buddhist and Muslim, Jewish and Christian, Pagan and atheist.

And so, despite the warnings, I stayed curious about different traditions, learning about other religions as I dove deeper into my own.

As I’ve made religion my profession, I’ve also come to appreciate how interreligious dialogue has changed over the years and how it is far from the caricature I was brought up to believe it was.

On the occasion of the 2023 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago (August 14-18), I shared some thoughts on interreligious dialogue and its role in the contemporary world on my column, “What You Missed Without Religion Class.”

Interfaith dialogue often gets a bad rap as a project concerned with surface level “feel good” conversations. Today, interreligious dialogue (a more widely preferred term) has grown into a multifaceted and critical field of interaction with real-world impact and implications for your life and mine.

In the beginning, we argued over origins

At the most recent meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention in New Orleans, Louisiana, the nation’s largest evangelical denomination upheld its policy of not ordaining women as pastors.

After voting to finalize the expulsion of churches with female pastors, Southern Baptists voted to further expand restrictions on women in church leadership, potentially opening up hundreds of new churches to investigation and expulsions.

The SBC's policies state, "While both men and women are gifted for service in the church, the office of pastor is limited to men as qualified by Scripture."

As gender studies professor Susan M. Shaw wrote for The Conversation, such “battles over women in ordained ministry in the SBC are not new.” The matter of women’s roles as preachers, teachers and leaders at large have been debated by Southern Baptists since the convention’s founding in 1845.

One of the points used to undergird the argument to exclude women from ordination is a doctrine known as the “orders of creation” (or “order of creation”), which affirms God’s role in establishing social domains in the family, church and society through the very “order” of creation of the world, as recorded in the book of Genesis.

In 1984, as fundamentalists gained greater control, the SBC passed a resolution against women’s ordination. The resolution said that women were excluded from ordained ministry to “preserve a submission God requires because the man was first in creation and the woman was first in the Edenic fall.”

Indeed, the discourse around origins can be powerful.

In this post from “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I explore the conflict over origins and show how dealing with the genesis of the universe isn’t necessarily about what happened (or not) in the past, but very much about ordering life, traditions and communities in the present.

Of αιτία and the κόσμος

For word nerds, etiology – when used within the realm of religious studies – refers to a quasi-historical or mythical description of origins. Drawn from the Greek term αιτία, these stories have to do with the cause or why of something — that which is responsible for a present condition, the reason for today’s state of affairs.

One type of etiology is a cosmogony, which is a myth on the origins of the cosmos (κόσμος) – a story that tells us how the grandest system of them all came into being in the first place.

When I first started studying religion, I was fascinated with cosmogonies.

I devoured stories like that of Rangi the Sky-father and Papa, the Earth-mother from the annals of Maōri teachings (akoranga), perused narratives about humanity’s creation from reeds (uthlanga/umlanga), as told among the Nguni peoples of Southern Africa (Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi), and dove deep into Ancient Near Eastern origin myths like the “Enuma Elish,” the Hindu “hymn of creation” from the Rig Veda, and Maya myths like the Popol Vuh.

Coming from a Christian household, my original intentions were to compare these cosmogonies to that with which I was raised. I wondered what different traditions had to say about the origin of everything that ever existed and what these stories had to say about the relationship between humans and the cosmos.

Why origin stories matter

But my early investigations were plagued by a fatal problem: I was searching for an essence, archetype, or sacred thread that would link these various stories into one grand narrative or speak to some fundamental truth about how the Divine is related to life in the world today.

Today, some two decades after I first heard the story of the Rainbow Bridge — a Chumash narrative about how people came to the mainland from Limuw (Santa Cruz) Island after being created from the seeds of a magic plant by Hutash, the Earth-mother — I’ve come to view these texts from a very different perspective than what my previous lens could offer.

These texts matter, but less because of what they have to say about the essential nature of things (which I was in search of) or whether or not they are historically verifiable.

As a point of fact, the interpretation of creation myths has changed over time. Take, for example, how the “Creation story” in Genesis has been seen as everything from a poem to a quasi-scientific textbook concerning earth’s origins and used as a prooftext to support views ranging from “young Earth” creationism to evolutionary creation, “old Earth” creationism to intelligent design.

Instead, cosmogonies and etiologies matter because they provide a window into how communities, or the students and scholars who study them, utilize such stories to situate themselves in the world and in relation to others.

The search for origins always comes from a specific place, interested in defining truth from its own position. And, in doing so, establishing the otherness between “us” (placed perfectly in the perspective of eternal history) and “them” (hopelessly askew in the etiology of things).

As the SBC example shows, these accounts use some narrative from the past (i.e., the world’s creation, a nation’s origins, the conception of a community, or the genesis of a particular place or geological formation) to authorize a position in the present.

In other words, these origin discourses are not actually about how something came into being, but instead about legitimizing or benefitting the position of the one who is telling or hearing the tale today.

Comparing cosmogonies, evaluating etiologies

There are innumerable etiologies floating around the world. The student of religion is welcome to read and study them. In fact, it is critical that the student of religion pays attention to origin stories. But not for the reasons we might think.

Rather, we should approach them as just-so stories that authenticate contemporary discourses or positions of power in the fertile soil of a past beyond our reach and understanding.

In the case of the SBC, that means reminding women that they come after men. And, further, because of that “fact,” they are not meant to serve as pastors.

The student of religion’s task in studying cosmogonies like that is to make sense of alternative orders of reality and how they shape social realities in contemporary contexts.

Above all, as we compare cosmogonies and evaluate etiologies, we should be careful to approach them as very human attempts at producing a comprehensive vision of ultimate importance. Even describing them carries the risk of uncritically reproducing them and therefore, legitimizing them.

We must always remind ourselves that as these stories are told and retold, studied and deciphered, they are meant to not only remind hearers of their place in the cosmos, but to form persons for a particular kind of religious, social, political, or economic life.

And finally, a humble student of religion will remember that’s as true of our evaluations as it is of the origin stories we study.

PHOTO courtesy of Francesco Alberti.

From Mecca to Mount Kailash: The Enduring Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World

As the summer travel season starts and the annual Hajj — the Islamic pilgrimage to holy sites in Saudi Arabia required of all Muslims who are able — is expected to begin on June 26, it seems a good time to reconsider the concept of “spiritual travel” or, more specifically, pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage is generally defined as a journey with a religious purpose, often taken to a place of spiritual significance involving certain rituals or paths.

More broadly, pilgrimage can be any journey and its associated activities, undertaken by people to and from one or more places made meaningful by the pilgrims themselves.

Though long associated with European Christianity in Western academia, or perhaps with significant sacred shrines like Mecca or Mount Kailash in Tibet, pilgrimage can also include trips to seemingly mundane places or movement to and from otherwise unexceptional locations.

Furthermore, pilgrimage is not restricted to institutional religions. Some pagans and others with a focus on old traditions (i.e., Reconstructionists or "Recons") travel to lands where they believe original gods were from or to ancient sites of significance. For example, a Greek Recon may go to Greece; Celtic practitioners to standing stones in the United Kingdom; heathens to Iceland; African traditionalists to significant sites in South Africa or Uganda.

Visits to nonreligious sites have also become increasingly popular as a form of pilgrimage in recent years. Large numbers of people find meaning in traveling to memorials of suffering, pain and bloodshed like the 9/11 Memorial in New York City or the “Killing Fields” of Cambodia. There are also pilgrimages to places linked to such pop culture icons as Elvis Presley, Susan B. Anthony, Steve Prefontaine or Taylor Swift.

With all these varying expressions, pilgrimage — like other religious rituals and phenomena — is what we make it. Less than looking for the transcendent meaning or chasing after miracles, the student of religion should pay attention to the human elements of spiritual travel: Things like tourism and economics, politics and place.

The importance of place, people and politics.

Journeys to holy sites and major religious celebrations can be shot through with multiple meanings, personal motivations, and traveling trajectories.

Take, for example, the pilgrimage experience of those who make the expedition to Tepeyac hill in modern-day Mexico City. There, each December, pilgrims from all over the world gather to celebrate the annual feast of the Virgen de Guadalupe, joining a centuries-old Catholic tradition of celebrating what is known as “the miracle on Tepeyac Hill.”

According to celebrants, it was at that spot that May, the mother of Jesus, appeared to a Nahua villager named Juan Diego. The cloak she gifted him included an image of herself as a radiating, brown-skinned goddess robed in stars. Despite its linkages with Spanish colonialism and forced conversion, the image and festival have enduring cultural importance in Mexico. After 500 years of devotion, the annual celebrations are some of the most robust in all of Catholicism.

But each year, it is not only Catholic devotees who make the pilgrimage to the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City. So do some of the city’s Sufis. According to religion scholar Lucía Cirianni Salazar, members of the Nur Ashki Jerrahi tariqa in Mexico City join millions of others to commemorate the Virgin’s apparition. Justifying their presence from a universalist perspective, the leader of the group — Shaykha Amina — told Salazar that the location represents one of the most powerful places for connection to the “one God.”

This example reminds us that far from removing people from the world, pilgrimage is all about places in the world. Less about the world beyond, pilgrimage is often very much about places we inhabit and fill with meaning.

This means that although often associated with the extraordinary and faraway, pilgrimage sites can be local and surprisingly unremarkable. What matters is context and the meaning people give such locales.

Pilgrims frequently journey with the expectation of miracles or receiving spiritual blessings from contact with significant religious figures, symbols and artifacts (e.g., relics or icons). Or they expect the travel itself will provide some transcendent benefit. Even so, pilgrims' progress and practices are intimately tied up with the worldly dynamics of tourism, local economies and the embodied experience of bumping up against fellow pilgrims with blood, sweat and tears along the way.

Pilgrimage also has powerful political overtones. For example, the disputed site of Marian pilgrimage in Medjugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina, is suffused with symbols of Croat nationalism, featuring prayer beads in national colors and Mary set against the backdrop of a Croatian national flag on everything from pillows to pillboxes. Still, despite its contentious place in the civil war of the 1990s and ongoing tensions in the Balkans, Medjugorje has become a huge draw for pilgrims drawn to its calls for peace and the renewal of faith along with prophecies of divine intervention.

Other pilgrimages such as the Hajj become playgrounds for political football, with nation-states and power brokers fighting over everything from logistics and management to the miracles and blessing associated with sacred sites.

The politics of pilgrimage are also at play around physical boundaries and borders that some spiritual travelers must contend with. Beyond visas and travel quotas, pilgrims must navigate the vicissitudes of state power and the various impediments that are put in place to deter, capture, or otherwise manage and control traveling bodies.

Those journeying to and from pilgrimage sites are often on the margins of official religious communities. Instead, their motivations for movement are linked to personal spiritual trajectories, frequently with little or nothing to do with institutionalized religion.

The physicality of pilgrimage must also be taken into consideration. To return to Tepeyac, Elaine Peña talks about Marian pilgrims’ “devotional labor.” Peña writes of “the moments of pain and discomfort” for pilgrims making their way to offer devotos to the Virgin of Guadalupe every December — “walking on blistering feet, proceeding on injured knees and cramped legs, with growling stomach and salty saliva, with too much light and too little sleep.”

Enjoy the journey.

As I write this blog, I am already starting to plan for my own travels this summer, including a visit to the largest mosque in the United Kingdom and some off-the-beaten-track churches in Berlin, Germany. While not explicitly pilgrimages, these trips will be filled with divine intimations.

This means I will be looking out for some of the very things mentioned above: The importance of place, the role of politics and economics and the position and plurality of bodies that inhabit a space or move around, through and within it.

Perhaps you too are getting ready for a trip. Maybe, you are embarking on a pilgrimage of your own this summer. As you do so, try to not only savor the spiritual importance of such travel, but the very human aspects of how these journeys are made holy in the midst of the mundane.

FURTHER READING:

•Read “A pilgrim’s progress: Resources for reporting on religious journeys,” from ReligionLink.

•Explore the Routledge Studies in Pilgrimage, Religious Travel and Tourism book series.

•Read Powers of Pilgrimage: Religion in a World of Movement, by Simon Coleman (2022).

•Explore the Oxford Bibliography on Pilgrimage for numerous resources, studies and possible sources.

What One Man Learned About Religion Visiting Every Country In The World

May it be Your will, Lord, our God and the God of our ancestors, that You lead us toward peace, guide our footsteps toward peace, and make us reach our desired destination for life, gladness, and peace. … May You send blessing in our handiwork, and grant us grace, kindness, and mercy in Your eyes and in the eyes of all who see us.

The Traveler’s Prayer — also known as the Wayfarer’s Prayer, or Tefilat Haderech in Hebrew — is an invocation said at the onset of a journey. Customary to recite when one embarks on a long trip, the prayer is a request for safety and protection but also that the traveler would be a blessing to those they meet in the course of their voyage.

Daniel Herszberg, a 30-year-old doctoral student from Australia, said the prayer is a common one among Jewish travelers, and the “beautiful text” traveled with him as he visited all 197 countries around the globe over the last 10 years.

As he finished his feat after setting foot in Tonga in March 2023, Herszberg became the 145th most travelled person in the world. Along the way, he also amassed 79,000 Instagram followers at @dhersz. He also became an unofficial student of humanity, treasuring the opportunity to learn more about the world’s religions and connect with Jewish communities scattered across the globe.

From Addis Ababa to Tehran, Herszberg visited synagogues, schools, cemeteries and Sabbath services in hospitable homes. In Suriname and Poland, in Pakistan and Sudan, Barbados and Brazil, Herszberg not only discovered cherished archives and legacies but connected with locals who shared their stories — both lived and long forgotten. In some instances, he was the first person to have visited Jewish heritage sites in decades.

It’s a responsibility the 30-year-old global citizen is quite philosophical about, whether in terms of what it means for the diaspora as a whole or who he is as a modern Jewish traveler.

“No matter how far you travel,” Herszberg said, “you always return to where you began — home.”

Barely Anyone Reads the Bible in Germany. So Why Are Luther Bibles Selling So Well?

From “better an end with horror than a horror without end” to expressions like bloodhound, baptism of fire, and heart’s content, the German language is peppered with idioms from a source that’s more than 500 years old: the Luther Bible.

A translation by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther, the Bible continues to be a touchpoint for German culture, politics, and language. And in 2022 — over 500 years after its initial publication — it was a bestseller yet again.

According to the German Bible Society (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft) in Stuttgart, they circulated 130,000 copies of the Luther Bible in 2022, accounting for almost half of their total distributions that year.

“After five centuries, it remains the most popular Bible translation in Germany,” said the German Bible Society’s General Secretary Christian Roesel (Rösel), “it is and will remain a classic.”

While the Luther Bible may remain a definitive example of German literature and hold a special place in its national psyche, ordinary Germans often know its catch phrases better than its contents. According to a 2017 opinion poll conducted by Insa-Consulare (Erfurt) and the German Christian magazine “Idea,” only four percent of German adults read the Bible every day. 70 percent say they have never read it once.

That begs the question, at a time when Bible sales are generally falling — related to a decline in Christianity’s share of the overall German population — why do so many Germans keep buying it?

Photo courtesy of Nathan Engel via Pexels.

Religion at the 2023 Academy Awards

When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its nominations for the 95th Academy Awards in January, contenders included several movies with religion angles and numerous actors with faith backgrounds.

A short list for the ceremony, to be held March 12, 2023, includes the eco-spiritual themes of Avatar: The Way of Water, revivalist roots in the Elvis biopic starring Austin Butler and Tom Hanks, themes of “faith and fatness” in The Whale with Brendan Fraser, the Bible Belt cultural cues that are felt but never fully seen in To Leslie’s melancholic storyline, and confessions and questions of whether God cares about miniature donkeys in The Banshees of Inisherin.

That’s not even to mention Stranger at the Gate. Directed by Joshua Seftel, the film is about an Afghan refugee named Bibi Bahrami and the members of her Indiana mosque, who come face to face with a U.S. Marine who has secret plans to bomb their community center. That’s when the Marine's plan takes an unexpected turn. The moving real-life story is considered a favorite in the best documentary short film category.

Beyond awards season, 2023 has a slew of new religion-related releases sure to catch audiences’ attention.

It’s safe to say that if you head to the movies – or catch the Academy Awards ceremony – this year, you’re likely to run into religion. But what might we learn about religion and culture from this year’s many intersections between faith and film?

Andrew Nemr Taps into Story

Andrew Nemr is breathless. Sweating profusely. Focused.

Swinging his arms and shuffling his feet, he is dancing across a stage made of four, square, darkly and deeply scuffed wooden gig boards, shedding tears, and telling his life story. Through the panting, pointed moves, and visible pain, Nemr isn’t just telling his story, but inviting the audience into it.

It’s 2017 and Nemr is performing “Rising to the Tap,” a one-man show produced in collaboration with the Flying Carpet Theatre in New York City. Combining tap, storytelling, and physical drama, Nemr does more than dance. He taps his away across continents and time, recounting the beats and drops of his own narrative in rhythm and spoken word, stomps, and flicks of the toe.

In the show, he takes the audience from the war-torn streets of Lebanon to the quiet suburbs of Edmonton, Alberta, from the dizzying heights of dancing with tap gods in New York City to his own inner journey toward deeper community across borders and boundaries.

Five years later, in 2022, Nemr is still performing the show. He’s also still writing that life story, improvising new chapters, and inviting others into a grander narrative about setbacks, growth, and shaping the world for good.

PHOTO: Ken Chitwood

Oppression or Liberation? Sweating Over Modest Clothing

Sitting with Soraya under the shade of a palm tree along Balneario del Escambrón’s sun-soaked sand in San Juan, Puerto Rico, I could barely stand the heat.

It was 88° F (31° C) with high humidity. Sweat was pouring down my face as I listened to her talk about her experience as a Puerto Rican convert to Islam.

Amidst the discussion, she noticed my perspiration and laughed. “Hermano, you think you’re hot?! Imagine being dressed in a black abaya [loose over garment] and hijab!”

Bringing the topic up, I asked her why she chose to wear hijab — or Islamic headscarf. Soraya replied, “before I became Muslim, men were always judging my body by its curves, by how tight my clothes were and how round I was in certain places. Wearing abaya donning the hijab, takes those evaluations out of the conversation and forces people to take me for who I actually am, what I say, what I do — not what I wear.”

Even so, Soraya still gets stopped on San Juan’s streets and asked about her clothing, her religion, or whether she feels “oppressed.”

For many, the “controversial fabric” is a symbol of subjugation and segregation. Especially right now, as protests continue to rage in Iran after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Ahmini who was killed while resisting the country’s compulsory laws forcing women to wear hijab, the headscarf has once again become a trademark of tyranny and functional emblem of fundamentalist religion.

And yet, for millions of religious women, headscarves, veils, and others forms of conservative clothing remain a prized tradition, a fashion statement, or — as with Soraya — a means of liberation.

In my latest piece with Patheos, I explore the material contexts and colonial pasts that are imperative to keep in mind when discussing hijabs, veils, and other forms of modest, religious dress.

From the film, “Casino Royale” (2006).

The Theme is Religion, James Bond Religion

When you think of James Bond, you probably don’t reckon with whether or not the super spy is religious or if spirituality plays a major role in his action-filled escapades.

But if you look for it, religion is everywhere in James Bond:

In the novel You Only Live Twice, Ian Fleming casts James Bond in the role of a savior, prophesied by Shinto priests and embodying the saintly personage of the Catholic, dragon-slaying hero St. George.

Live and Let Die — both the book and movie — heavily feature vodou and obeah, with a 007-emblazoned, customized tarot card deck specifically designed for the film.

There is a “priest hole” and chapel on Bond’s family Scotland estate in the movie “Skyfall” (2012).

Bond battles with a man dressed as a Nio guardian statue in the film, “The Man with the Golden Gun” and traipses through Cairo, Egypt’s Ibn Talun mosque in “The Spy Who Loved Me.”

In 2015’s “Spectre,” Bond replies to his love interest Dr. Madeleine Swann's question, "Why does a man choose the life of an assassin?" with, "Well, it was that or the priesthood."

The list could go on, but suffice it to say: James Bond has a long and complicated relationship with religion.

On the occasion of the 60th-anniversary of the world premiere of the first James Bond film Dr. No in 1962 (October 5, 2022), I take a look at religion in the Bond universe and consider what we might have to learn about religion — and the world-famous super spy — in the process.

On a Wing and a Prayer

Amid the hustle-and-bustle of checking in, making your way through the obstacle course that is security, and divining where your gate is, you might not have time to grab a bite to eat or sneak in a quick massage, let alone have time to settle yourself for prayer.

But, across the U.S. — and throughout the world — airport chapels, prayer rooms, and interfaith spaces offer travelers an opportunity to do just that: to meditate, catch a few moments of quiet contemplation, or perhaps beseech the travel gods for a bit of mercy when flights are canceled, or luggage lost.

According to sociologist Wendy Cadge, airport chapels had their genesis in the daily devotional needs of Catholic staff working in the airline business. She wrote of how initially, airport chapels “were established by Catholic leaders in the 1950s and 1960s to make sure their parishioners could attend mass.” The very first was Our Lady of the Airways at Boston’s Logan airport, built in 1951.

Today, major transit hubs across the world offer some sort of spiritual respite for the busy traveler.

Pew Research Center found that more than half of the U.S.’s large hub airports (catering to 1% or more of annual air passengers) offer a chapel or interfaith prayer room of some sort. These include standouts like San Diego’s meditation room “The Spirit of Silence,” Orlando’s former, centrally located prayer room, San Juan, Puerto Rico’s decidedly Catholic chapel, or John F. Kennedy Airport’s synagogue, the only one of its kind in the Americas.

Internationally, you can find stunning examples like the Buddhist meditation space at Taiwan’s Taoyuan Airport, Berlin’s Room of Stillness and its formidable fire-brick interior façade, or the new Istanbul airport’s ecologically-certified Ali Kuşçu mosque, which can fit up to 6,230 people for prayer.

Far from cheaply-packaged single-serving spirituality or simply a security threat, airport chapels, prayer rooms, and interfaith spaces offer a chance to reflect on how we define religion, both at home and abroad. Their persistent popularity, and their place in our religious imagination, exhibit the pluralism, plasticity, and politics that typify global religion today.

Visiting Every. Church. In. Berlin.

When Berliners Piet and Ulrike Jonas travel abroad, they head into local churches to gawk at stained glass windows, ponder over ornate altar pieces, and discern the meaning of devotional art.

“It is a way for us to get to know the place,” said Piet, “to begin to understand its history and the people who lived there.”

With church visits featuring so prominently in their vacations, Piet and Ulrike wondered if they might start doing the same in their home city.

And so, one-by-one, they began to look in on Berlin’s churches. What started as a hobby quickly turned into a goal-oriented project: to visit every church in Berlin.

Alle Kirchen Berlins was born.

According to their website, their project is simple. “We want to see all the churches in Berlin from the inside,” they wrote. According to their count, that means visiting some 450 locations. As of January 2022, they were at number 381.

The project, however, is not explicitly religious in nature. Nor is it specifically historical, architectural, or social. Instead, Piet and Ulrike said it’s about getting to know Berlin.

Along the way, they are encountering the city’s diversity and development, it’s eclecticism and surprising spiritual effervescence.

“One would not think that Berlin is an especially religious city,” said Ulrike, “and yet we are finding out just how important religion has been and still is.

More than showcasing some of the most remarkable, interesting, or site-seeable places of worship, Alle Kirchen Berlins provides insight into how we understand and negotiate what counts as religion. Moreover, the project highlights how our encounter with religion is part of the way in which contemporary societies — and cities — organize and understand themselves.

Specifically, Piet and Ulrike’s project highlights how city dwellers determine what counts as sacred and secular, how immigration has long been a part of shaping urban religious expressions, and how the notion of religion and the notion of a city are entangled with one another, the one shaping the other and vice versa.

PHOTO by Stella Jacob on Unsplash.

The age of "spirit tech" is here. It’s time we come to terms with it.

The electrodes are already attached to your scalp, so you settle into a seat that reminds you of the one they use at the dentist’s office. On the other end of a series of cords is a machine where a technician sits with a clipboard and a range of blinking and bleeping devices.

No, you’re not about to start a medical diagnostic exam.

You’re about to meditate.

Sound surreal? If so, welcome to the brave new world of “spirit tech,” where a range of researchers and practitioners are using brain based tech to “trigger, enhance, accelerate, modify, or measure spiritual experience.”

In their new book — Spirit Tech: The Brave New World of Consciousness Hacking and Enlightenment Engineering — Wesley J. Wildman and Kate J. Stockly take a stimulating journey into the technology that could shape our spiritual futures.

Investigating the intensifying interaction between technology and religion, they talk to innovators and early adopters who are "hacking the spiritual brain” using ultrasounds to help practitioners meditate or experimenting with “high-tech telepathy” to build a “social network of brains.”

Not only did I get the chance to read the book, I also sat down with a one-on-one interview with Stockly about how spiritual entrepreneurs and tech-savvy religious practitioners are using technology to modify spiritual experiences.

While critics may question “spirit tech’s” efficacy, elitism, and ethics, Wildman and Stockly are careful to note that religious people have always used tools — from mantras to mandalas, prayer beads to palm reading — to enhance spiritual experience. The difference now, they write, is the sheer number of “customizable and exploratory practices at the threshold between cutting-edge tech and the soul,” from synthetic psychedelic trips in lieu of Holy Communion to LED orbs that create connection between congregants.

Wildman and Stockly do not pretend to have it all figured out — spirit tech’s ability to balance innovation and enlightenment, they say, “is still being written” — but their thought-provoking introduction to the brave new world of transcendent tech gives both pious pioneers and defenders of traditional religion something to consider as they imagine the future of spirituality in the 21st-century and beyond.

Photo courtesy Oberammergau Passionspiele, via Christianitytoday.com.

Growing Hair for Jesus, German Village Plans for 2022

Jesus is thrilled to see you again in May 2022.

Or, at least, Frederik Mayet, the man who will play Jesus in the 42nd Oberammergau Passion Play season next year, is excited to welcome attendees — many of them pilgrims — back to his village, after a two-year postponement of the play due to the coronavirus.

The play started in 1633, is a reenactment of the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus, with performances taking place once every 10 years. In the intervening years, it’s only been canceled a few times: once for the Franco-Prussian War, once for each of the World Wars, and last year, because of COVID-19.

“I’m really looking forward to see people coming together again,” said Mayet, “we worked really great together as a village being on stage for half a year before the lockdown and then suddenly, from one day to the next, you don’t see anyone for weeks and months.

“We are optimistic about next year, because we really want to have this situation back,” he said.

The passion play is now set to run May 14 to October 2 next year. The actors of the village formally began to prepare last month on Ash Wednesday, when director Christian Stückl put out an official “hair and beard decree.”

The decree instructed all the local actors to “let their hair grow out, and the males to also grow a beard.”

Mayet said, “with the hair growing, you start to grow into your role as well.”